Easter is often a time of

disappointment for me. It is easy to

plunge myself – or rather, to let myself be absorbed – into the ineffable joy

of the Paschal Mystery, especially if I am able to attend a liturgy which at

least attempts to reflect the eternal glory of that momentous occasion. But Easter, most notably the later days of

Easter week, is sad because of my incapacity to communicate this joy. Joy is deepened and broadened when shared;

but this joy is, after all, ineffable.

This morning I thought about trying

to teach my son, who is only a year old, something about Easter. He is smart enough to learn names and places

and customs attached to them, people and animals and what they do, but I

realized that he is not old enough to understand Easter. Why not?

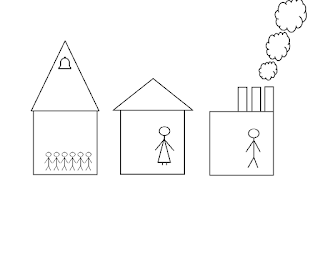

Little children can understand Christmas to a degree; that a special

little baby was born. They can

understand Halloween, that we dress up and act like other, special people. But not Easter…

My little child cannot understand Easter, not

because it is terribly complex, but because he does not yet know enough about

evil. The joy and glory of Easter is

only as apparent to us as the evil which Christ has overcome. A one-year-old knows almost nothing about

evil: He may know hunger, discomfort,

loneliness, and fear, but his experience only amounts to small samples of these

things. He does not know real pain,

abandonment, anguish, or dread. He does

not know what it is like to have no home, no good friends, and no clear

future. He does not know what it is like

to worry about feeding his family. He

does not know what it is like to look into the eyes of someone he loves,

knowing beyond all doubt that this will be the last time. Any child can feel love and gaiety and

excitement, as they will, hopefully, in these coming days of Eastertide, but it

will be a superficial gaiety compared to what the adult Christian should know.

That an adult has a greater capacity

for joy than a child points to another, more important fact. The reason that adults have a greater

capacity for joy is precisely because they understand and have experienced more

evil. In regard to the Easter Mystery,

which is the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, the joy which it demands has no

limit. This is because the Resurrection

marks the limit of all evil: Jesus

Christ, Who is a flesh-and-blood human being, has set the precedent for all

other human beings. No matter what evil

things happen to us, we have our own resurrection to look forward to, merited

by Jesus Christ on Calvary and established in that moment which Easter

continues to remember.

An epithet which I would like to

see propagated (which perhaps would come second in weight only to “the

Death-Slayer”) is “the Hero of Eternity.”

Our present culture understands the notion of ‘hero’ well and continues

to pay homage to heroes living and dead, as well as creating an abundance of

literature and popular mythology which centers on heroes. Whatever heroes we honor, be they warriors or

martyrs, we understand their heroism according to their deeds and

accomplishments. In another essay, I expounded

the idea of Jesus Christ as the greatest hero of which can be thought, because of

the greatness of His victory. What I did

not realize at the time, however, was the infinity of that victory. This comes to light against the darkness of

evil, because without evil there can be no hero.

We are reminded of the famous line

from the Exsultet, remembering Adam’s sin, “O Happy Fault, which merited for me

so great and glorious a Redeemer!” Our dark and evil

history becomes a cause for joy and consolation in the light of Christ’s

redemption. But this truth runs as deep

as we dare to look. Many of us honor

veterans, if not for what they were called on to do, at least for the horrors

they were made to endure: We know that

we cannot fully appreciate their sacrifice because our empathy only goes as far

as our imagination. The same holds true

for police men: We would rather not know

what they have to see on a regular basis, even for our sake. Every Good Friday, though, we are forced to

imagine the suffering and death of Christ.

For most of us, it is at worst mildly uncomfortable. We know we cannot fully appreciate what

Christ endured. But what about what

Christ has transformed? We are reminded

that His passion and death were not arbitrary, and not even regretful, but that

there was something about that episode which changed the meaning of evil. Before we were redeemed by Christ, we

deserved everything we got: That is,

because of our despicable nature, because of our sin, we could not even begin

to repay what we owed to God nor endure enough hell to buy our way out of

it. After Christ’s redemptive suffering,

every evil we endure is a bonus; something to add to Christ’s suffering. Evil now means something.

And neither can it be the end. If there is no depth to man’s capacity for

evil, then Christ’s Goodness is beyond any depth. There can never be enough evil to undo what

Jesus Christ did. But it is more than

this: A child cannot know the joy and

hope of the Resurrection because he does not know or fear death. But as we grow older and more weary, so grows our joy. The more fear and death there

is in one’s life, the more cause one has for joy and hope. Every evil that can be imagined becomes fuel

for the unquenchable fire of God's Love: The more we have to worry

about, the more that bothers us, the more that evokes our anger and

indignation, the more cause we have to be dizzy with excitement. The greater our slavery and subjection, the

greater our salvation. This terrible

world is not merely a place to practice patient endurance, it is a counterpose; a dark backdrop to eternity, which will shine all the brighter on our darkened

eyes.